Alice Josephine Zinns and Edwin Stull Sylvester

EDWIN STULL SYLVESTER, son of SARA CUNNINGHAM STULL and GEORGE SYLVESTER, was born May 18, 1884 in Milwaukee, Milwaukee, Wisconsin,4653 and died March 26, 1971 in Hackettstown, Warren, New Jersey.8875 He is buried in George Washington Memorial Park, Paramus, Bergen, New Jersey.8875

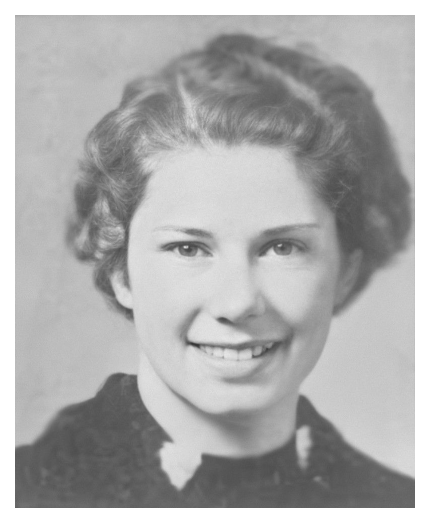

He married ALICE JOSEPHINE ZINNS on November 20, 1907 in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin.4818 She was born March 3, 1884 in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin,8160 and died September 2, 1963 in Glen Rock, Bergen, New Jersey.8352, 12289

Children of ALICE JOSEPHINE ZINNS and EDWIN STULL SYLVESTER:

- GEORGE STULL SYLVESTER, b. August 22, 1908, Milwaukee, Milwaukee, Wisconsin;2970 m. BARBARA THOMPSON on November 17, 1948 in Stamford, Fairfield, Connecticut9721; d. June 19, 1961, Niles, Berrien, Michigan.2970

- ANITA JOHNSON SYLVESTER, b. February 26, 1910, Milwaukee, Milwaukee, Wisconsin;8160, 12278 m. JOHN WESLEY LAMPE on January 31, 1936 in Glen Rock, Bergen, New Jersey9718; d. July 5, 1956, Glen Rock, Bergen, New Jersey.8352

- BARBARA ELIZABETH SYLVESTER, b. August 20, 1919;56 m. MARINUS JOHN VANDEN BOSCH on July 5, 1941 in Glen Rock, Bergen, New Jersey9719; d. January 25, 2008.56

George

Anita

Barbara

Newspaper Articles

Washington Post, April 19, 19149722

A FLIGHT FOR LIFE FROM TORREON

Desperate Race Against Time and Escape by Automobile from Doomed City

Truth seems always to be robbing fiction of its glamour. One who doubts it and believes that the most stirring tales of daring and danger originate in the fertile brains of unreasonable scribes should have attended a recent dinner where a score of "exiles" gathered for a reunion. The "exiles" were full-fledged American citizens banished from faraway Mexico. There they had known one another before the serenade of the light guitar gave way to that of a bombarding cannon. They had heard both, and even as they listened to the melodious strains of "La Paloma," the popular Mexican anthem which the restaurant orchestra played for them, they seemed to hear with a sense finer that that bestowed by the ear the thundering hoofs of the rebel cavalry under Gen. Francisco Villa, which even then was closing in on the once fair city of Torreon, whence these "exiles" came.

Among the most interesting of the stories told of siege times and escapes to the border was that related by Edwin Stull Sylvester, now living in 247 West 104th street. With his wife and two children, Anita, 4 years old, and George, 6, they narrowly missed death when Gen. Villa besieged Torreon last July, and there flight across the Mexican desert for miles in an automobile was beset by adventures which might well furnish the plot for a novel of daring and danger.

"I lived with my family near the rubber company's plant where I was employed," Mr. Sylvester said. "Our home was midway between one of the last battles of Villa's first campaign against Torreon. THe first warning I had of danger occurred about 4 o'clock on July morning when we were awakened by some one pounding on the door with the butt of a musket."

"If you don't open we will shoot," a voice cried in Spanish.

A Voice in the Night

My wife and I were silent, as were the children, for we had trained them to be quiet when we were disturbed at night, knowing that prowlers were after food and would depart if they thought the house empty. After banging the door again our early morning visitor departed. An hour later I was surprised on leaving the house to see our plant occupied by constitutionalist troops. Walking about two rods in the direction of the city, I saw a squadron of federal cavalry approaching at a gallop. I ran as fast as I could to my home, told my wife, and we placed the children in the only safe place in the house, that being in the brick-walled fireplace. Hastily we barred the doors and closed the shutters of the house, and none too soon. Scarcely had we finished the task when there was a jangle of sabers from the approaching cavalry and the rattle of musketry from the constitutionalists. Scores of the latter poured from the plant and just had gained the vicinity of our little home when they met the federals.

The House a Refuge

"The reports of rifles, screams of the wounded, moans of the dying, my little children huddled in the fireplace, and my wife in terror, fearing for their safety, made a picture which I shall never forget." Mr. Sylvester continued after a slight pause: "many of the dismounted soldiery sought shelter from a rain of bullets of our front stoop. Some of them tried to enter our home, but the doors and shutters fortunately held fast. Finally the constitutionalists were driven back and out of our plant, and only the dead and dying were left."

Mr. Sylvester said that the Mexicans are brave fighters and that during the engagement he saw several of them attempt to take a Maxim gun from the federals. When within a few feet of the gun it was touched off, and one soldier received seven bullets in his breast, despite which he staggered toward it until he fell.

With his wife, children, and six other Americans, Mr. Sylvester escaped from Torreon in two automobiles. Receiving President Wilson's warning that Americans should leave Mexico a month after it had been made, many Americans in Torreon believed that it meant sure intervention on the part of this government. Believing that interference in Mexican affairs might lead to a massacre of American citizens, many of the latter made hast to flee.

There was no train service, and after some difficulty, Mr. Sylvester and his friends purchased two automobiles—a Stoddard-Dayton and and Overland car. The manner in which they purposed to flee made the light traveling equipment necessary, consequently each of the party left with only a suit case. A limited amount of provisions and water could be carried, because it was necessary to take along a quantity of gasoline. Three weeks prior to their departure it had rained incessantly and the roads none too good in dry weather, practically were impassable near Torreon. To escape them the automobiles and their occupants traveled on a box car to a point of 20 miles northeast, the terminus of the railroad, and then the flight of nine days filled with peril from bandits, thirst, hunger, heat and mechanical mishaps began.

"We had smooth running for only an hour, and then our troubles started," Mr. Sylvester asserted. "There was an innocent-looking puddle of water across the road and it took us just three seconds to run into the middle of it. It took us seven hours to get out, for mud and slime clogged the machinery and came to the body of the car. With the assistance of the other machine and by wading waist deep in the mud we managed to be on our way again. But only for an hour. Dusk was falling as we entered a deep canyon. Scarcely were we between the towering walls of rock when a man stepped into the road and with a rifle ready for use, commanded us to stop. As we slowed up another peon on horseback appeared at a turn in the road. My wife grasped an American flag and showed it just as we stopped.

"What is that rag?" the man afoot said with a sneer.

"The American flag and we are American citizens bound for Saltillo, one of the party answered hotly.

"You cannot pass here," the horseman said. "Our chieftain has forbidden any one to pass. You must come with us to the mountains and wait. He will be here tomorrow afternoon."

"I think every one had his hand on a pistol," Mr. Sylvester continued. "We hesitated to shoot because of my wife and children.

"Leaning toward my wife I whispered in English, 'There seems to be no other way out of it. Shall we kill them?'"

"'Yes,' she replied calmly, adding, 'if there is no other way. But please lure them a short distance away so that their shots cannot strike the children.

A Dangerous Delay

"At this juncture in the conversation the chauffeur started his engines, whereupon both bandits covered my wife and children with their guns. The engine was stopped, and with a friend I asked the two men to follow us a few feet upon the canyon. We proposed to have it out there. However, as we walked my friend remarked that two peons would not be sufficiently foolhardly to try to hold up two automobiles, and we cane to the conclusion that their band must be near at hand. We offered each of the men a $50 United States gold certificate, which they took and allowed us to pass.

"It is lucky we did not attempt to shoot them," Mr. Sylvester said, "because we saw a score of bandits a few hundred feet away hiding behind rocks."

The party then drove until 2 o'clock the following morning. Late in the afternoon a pin was broken off the transmission of one of the machines. After two hours of work with a file and a monkey wrench a new one was made. Soon after dusk the party saw a ranch house, and upon reaching it were refused admission. The lone peon in charge of the hacienda told the Americans that roving bands were in the habit of stopping there for a carouse, and that they might make trouble for him if he harbored them. After much persuasion he agreed to let them remain. Mrs. Sylvester and the children occupied the rear room, while the men took turns at sleeping at staying on guard the remainder of the night.

Prior to the start the next morning little Anita and George were found playing with several pieces of pipe in the flower garden. Mr. Sylvester found that each pipe contained a stick of dynamite, and that the bombs evidently had been left there by the last party of foragers to stop there.

"We made splendid progress until that afternoon, when one of the machines was put out of commission by colliding with a pile of rock." Mr. Sylvester continued, "It was hopelessly wrecked and we abandoned it. Leaving three of our party and a Mexican chauffeur, we pushed on with my wife and children. At dusk we made camp, ate from our scanty supply of food, and waited until the moon rose.

Caught in a Water Hold

"The morning of the following or third day of our flight we were caught in another water hole. Without the aid of the other automobile we were powerless. For three hours we tried to dislodge the machine. Then we sat down, our hopes of escape settling as deep in a slough of dependency as our machine was in mud.

"To amuse him, I let little George shoot my revolver, and I fancy he made one of the luckiest shots he ever will make, for the noise attracted the attention of the driver of an overland wagon. He drove up to us with his six mules, and proved to be an American. We breakfasted with him, and then his team pulled our machine almost out of the mud. A peon passed with several more mules, and these, with the American's, got us out."

Mr. Sylvester asserted that the remainder of the day was passed in cross-country riding. It was necessary often to remove jagged rocks from the ground, so that the automobile could proceed. That afternoon saw the finish of the tires on the machine, and the remainder of the journey was made on the rims. Gobernador plants, which grow in profusion there, were wound about the rims and tied, and afforded some protection to them.

Toward evening they were stopped again by two armed men and directed to proceed to a hacienda several miles distant. There they saw 600 constitutionalist troops. After explaining to the commanding officer their predicament, they were given rooms in the ranch house, fed and treated with every courtesy. The next morning their three friends came in with the automobile that had been abandoned. They were riding in the machine, which was drawn by oxen. Their appearance caused much merriment among the troopers. Prior to their departure the constitutionalist leader offered them a escort of 50 men. They declined, fearing they might meet federal troops and that a battle would ensue.

"Leaving our three friends who had come in by 'oxmobile' to try for the border with a peddler, we rode away from the ranch house," the speaker continued. "We began to climb mountain ranges and our path was beset with rocks, streams, and other difficulties. That night it was cold. We dug holes in the ground and slept in them with our blankets around us. All about us we could see beacon lights and camp fires of the constitutionalist forces. The fifth day we were lost. I remember we attempted to climb a razorback looking hill and it was necessary for us to get out and push the machine. We could find no sign of a road or trail and wandered about quite a bit. That night our food had given out and we had only about a gallon of water."

Almost Exhausted From Hunger

They struck the Camino real, or Royal road, the following day and were making fair speed when 30 men rode out from behind a hill and stopped them. They told who they were and asked where they could obtain food and water. The soldiers gave them cigarettes and directed them to a ranch house 7 miles away, where they bought a few eggs and tortillas.

Then the Americans drove on the roadbed of what had once been the National Railroad of Mexico. Late in the day they came to an arroyo, or ditch, which was 12 feet wide and filled with water. It was necessary form them to walk several miles down the track to a pile of old crossties, and carry them back in order to build a bridge. After making a crossing they were stopped again by troops, who allowed them to proceed.

"We lived on one egg and one tortilla each on the following day," Mr. Sylvester asserted. "We passed several ranch houses, but for the most part they were deserted, and those inhabited had no food to give away, for the foragers of the army had successfully cleaned almost every larder in that section.

"We were all very much exhausted by this time. The sun was hot during the day, the country was dusty, with every now and then a dust storm. Water also was very scarce and the canned milk we brought for the children had given out. They were feeling the effects of the terrible journey and so was my wife.

"About noon on the eighth day we felt like shooting each other and giving up. We accidentally ran our faithful Stoddard-Dayton into the ditch and irreparably destroyed the engine. Everybody felt like crying except my wife, who suggested that a friend and I wald ahead and attempt to locate a ranch house or ranchman with horses in this most desolate country. Six miles away we found a ranch house and there rented two mules. With them we pulled the machine to the house, where we abandoned it. The mules were hitched to a light wagon and, with the peon driving. we set out for a ride of 40 miles to Saltillo. At dusk we camped and waited for the moon.

"With her bright rays to light us we began our journey up a steep mountain pass. My wife sat on blankets, while the children slept with their heads in her lap. In the course of about four hours we ascended three thousand feet, and it was terribly cold. But Saltillo lay in front of us. we could see tiny lights about the town and we knew these were campfires of the soldiers.

"At dawn we drove in. Straight to the hotel we went, and, by paying an almost fabulous price, we were given the best suite of rooms there. I shall never forget the joy and luxury of a bath. Everybody turned in and slept almost eighteen hours. The following morning, ten days after leaving Torreon, we boarded a train for the border. The train was loaded with the sick and suffering of the constitutionalist forces, but we had become accustomed to suffering. All we thought of was to get back to the gold old U. S. A., and I never thought Laredo, Tex. could look as good as it did to us when our train pulled in and we knew our trials and tribulations were over."

Obituaries

Sunday News, March 28, 19718875

Edwin S. Sylvester

RIDGEWOOD — Edwin Stull Sylvester, a former resident of the village and Glen Rock, died Friday at his home in Heath Village, Hackettstown.

A native of Milwaukee, Wis., Mr. Sylvester had lived in this area for almost 50 years before moving to Heath Village four years ago. After retiring from the Bank of New York in New York City, he worked as a school crossing guard in Glen Rock for 12 years. His wife, the former Alice Zinns, died in 1963.

Surviving are a daughter, Mrs. M. (Barbara) Vanden Bosch of Fayetteville, N. Y., and six grandchildren.

Interment will be in George Washington Memorial Park, Paramus. A private memorial service will be held.

Ridgewood Herald-News, September 5, 198312289

Mrs. Edwin S. Sylvester

Mrs. Alice Z. Sylvester, wife of Edwin S. Sylvester of 2 Bradford St., Glen Rock, died suddenly on Monday at her home.

Services will be private. In place of flowers, the family prefers contributions to First Church of Christ, Scientist, Ridgewood.

In addition to her husband Mrs. Sylvester is survived by her daughter Mrs. Marinus (Barbara) Van den Bosch of Ridgewood, and six grandchildren.

A daughter, Mrs. John (Anita) Lampe, and a son, George Stull Sylvester, predeceased her.

Census Records

| Date | Location | Enumerated Names |

|---|---|---|

| June 9, 19008865 | Milwaukee, Milwaukee, Wisconsin |

|

| January 6, 19209716 | New Rochelle, Westchester, New York |

|

| April 24, 19402705 | Glen Rock, Bergen, New Jersey |

|

| May 5, 19509717 | Glen Rock, Bergen, New Jersey |

|